As rents continue to rise at an alarming rate, affordable housing has become one of the hottest topics of political debate in Minneapolis. It featured prominently in last fall’s local elections, with candidates agreeing that the city is experiencing a housing crisis and that we need to build more affordable units. At Mayor Jacob Frey’s recent Affordable Housing Community Forum on Feb. 15th, 2018, he discussed the need for more “deeply affordable” units in Minneapolis – housing that, as he defined it, is set at 30% of Area Median Income (AMI). “Deeply affordable” certainly sounds nice, but the reality is not so good.

What is AMI?

Area Median Income, or AMI, is the midpoint of all household incomes in a region, meaning half of all households earn more than the median income and the other half earn less. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) determines what counts as a “region,” and for the Twin Cities, it includes Minneapolis and St. Paul as well as dozens of white, wealthy suburbs – 13 counties in total. In 2018, the AMI for our metro area was $94,300. This number, which our public officials and institutions want to use to set affordable housing guidelines, groups the poorest residents together with the wealthiest residents, and wealthier white people together with low-income people of color.

When developers, politicians, and non-profits talk about affordable housing, they mean housing that is affordable to households earning a certain percentage of AMI (commonly 60%, 50% or 30%). No matter what AMI is chosen, rent costs 30% of it (adjusted for the unit’s size). The actual low-income of residents is not factored into the rent calculations, as long as they don’t earn more than the chosen AMI level. So for example, 30% of AMI in the Twin Cities is $28,290 per year. People living in 30% AMI housing cannot earn more than that (unless they have 5 or more people in their family). As a result, $28,290 is the income that is used to determine rent levels in these “deeply affordable” units, even if the families actually living in those units earn less than that. (The income that qualifies for simply “affordable” housing is 60% of AMI, which is $56,580.) As mentioned above, the number of bedrooms in a unit will affect the ultimate rent levels as well. The greater the number of bedrooms, the higher the rent. While all this is confusing, the bottom line is that defining affordable housing in this way is problematic.

What’s Wrong with AMI?

There are some major problems with using AMI to determine affordability. The first is that by grouping an entire region’s population together, AMI ignores racial disparities that have resulted from centuries of housing and economic discrimination against minorities and poor people in the United States. Lumping our diverse central cities in with the more affluent, white suburbs produces an especially skewed result given that Minnesota has one of the worst racial disparities in the nation. In fact, while the AMI for a family of four in the majority-white Twin Cities metro area was $94.300 in 2018, the most recent census data lists the median income for black Minnesotan households is just $33,436, or roughly a third of the metro’s AMI. That’s a huge gap! Using AMI as a measurement to determine housing affordability for low-income families obscures the real needs of our city’s most vulnerable populations, and discriminates against people of color and poor people, and that’s by design. AMI-based housing, as opposed to truly income-based public housing, is part of private developers’ agenda to gentrify Minneapolis by making it unaffordable to people of color and poor people, so they can raise rents on everyone. The plan is to slowly eliminate the safety net of income- based housing for low-income families.

The second problem of relying on AMI to set affordable housing rents is that everybody earning less than the targeted percentage of AMI is left behind. According to the narrative pushed by developers, politicians, and the non-profit industrial complex, the most affordable housing we can provide is for households earning $28,290 per year. If that’s the case, then what happens to everybody earning less than that – those most in need? Don’t they deserve affordable housing too? A family taking in only $20,000 per year, for example, could still live in 30% AMI housing, but they’d be paying the same rent as households earning $28,290 per year. By definition, since they’d be spending greater than 30% of their income on rent, that housing would not be affordable to them. Therefore 30% AMI housing or above is only affordable to the narrow slice of the population earning exactly 30% of AMI or above, and no one else. Because of the racial disparities outlined above, the families getting left behind by the AMI-driven affordable housing paradigm are more likely to be poor, low wage workers, low-income people of color, as well as immigrants, refugees, seniors, and the disabled.

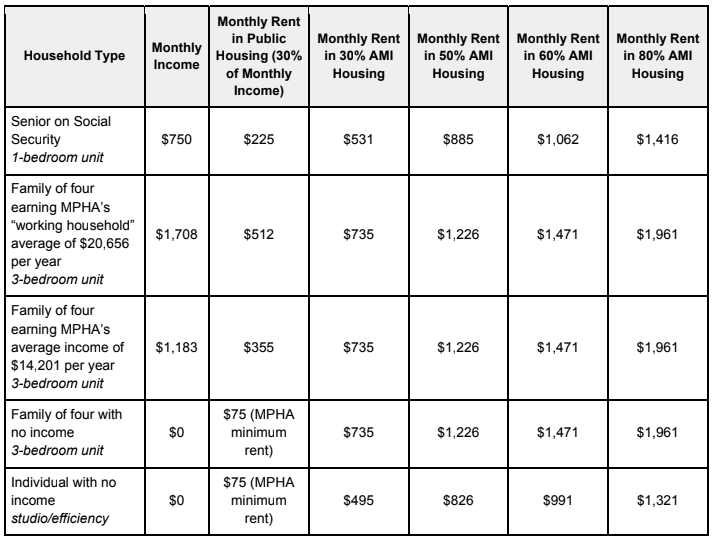

A further problem with AMI is that it discriminates against large family sizes. The greater the number of bedrooms, the greater the rent. So if two families have the same income, the larger family will get charged higher rent. The AMI model assumes that families can afford to pay more as their household size increases, but as anyone with kids will tell you, the opposite is true. A single mother, at the same income level, will have to pay higher rent if she has four children than if she has one child, even though the costs of raising four children are greater. This is discriminatory and burdensome on poor families. Public Housing vs “Affordable Housing” Thankfully, a better way to provide affordable housing already exists. Public housing, unlike privatelyowned “affordable housing,” charges residents 30% of their income for rent, no matter what their income is. So it is income based housing. Therefore, public housing always meets the definition of affordable, even if a household earns less than 30% of AMI ($28,290). This is good news for residents, whose incomes fall mostly below the 30% AMI threshold that would qualify them for the mayor’s “deeply affordable housing.” In fact, the average Minneapolis Public Housing Authority (MPHA) working household earns $20,656, and the average low-income MPHA public housing resident earns $14,201. Seniors that are on social security income take in just $9,000 per year, which is only $750 a month. Therefore, 30%, 50%, 60%, or 80% AMI housing would be deeply unaffordable to any of these residents in public housing including all working class renters that don’t live in public housing.

Let’s compare what people’s rents would look like in public housing vs. AMI housing:

It’s clear that public housing is a better option for low-income households.

Public Housing Under Attack

Because public housing is always affordable to low-income residents (due to being income-based rather than AMI-based), Defend Glendale & Public Housing Coalition (DG&PHC) wants to protect it. DG&PHC has been exposing MPHA’s plans to privatize Minneapolis Public Housing for years. MPHA claims that it lacks enough funds to keep public housing as-is, but instead of seeking out additional public funding, it’s selling out its vulnerable residents by pursuing a secretive and destructive privatization plan that would convert public housing to AMI housing. MPHA is now even openly admitting they prefer an AMI model over the truly affordable public housing model. In a past Twitter post celebrating Mayor Frey’s forum, MPHA writes:

“[Mayor Frey] kicks off tonight’s housing forum by saying it’s time to invest in deeply subsidized housing for families with 30 percent of area income. Who does more of that than anyone? Public housing!”

This is a lie. It is irresponsible for MPHA to imply that public housing relies on AMI measurements to determine rent levels when it does not (and cannot). Under federal guidelines, rent for public housing is determined at 30 percent of a household’s monthly income. By using such deceptive language, MPHA is laying the groundwork for its plans to convert public housing to private rental housing – a move which would jeopardize the well-being of its thousands of residents, as well as potential future residents of public housing. MPHA’s public housing waiting list had 12,701 people on it in 2016 and growing, a number which doesn’t even reflect all the people experiencing homelessness who could be provided an affordable home if public housing was expanded.

AMI-based housing is not a solution to the affordable housing crisis; it is an assault on the city’s poor and marginalized. The obvious solution is to have more public housing, not less, but that effort is being undermined by the very people in charge of public housing themselves: MPHA’s current Board of Commissioners and its Executive Director Gregory Russ. DG&PHC calls on the city of Minneapolis to put a stop to MPHA’s destructive plans, and fund public housing so that those most in need of truly affordable housing can actually get it.

References:

http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/mayor/vision/affordable-housing https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il/il2017/2017summary.odn http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2017/08/22/minnesota-racial-inequality/ https://www.twincities.com/2017/09/14/minnesotans-incomes-are-up-poverty-is-down-but-successes-remain-uneven/

http://www.danter.com/taxcredit/rents.htm https://metrocouncil.org/Communities/Services/Livable-Communities-Grants/2017-Ownership-and-Rent-AffordabilityLimits.aspx https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/DOC_11689.PDF https://twitter.com/MPLSPubHousing/status/964287671068778496 http://tinyurl.com/LIHTC-in-MPLS https://www.hud.gov/topics/rental_assistance/phprog